KAWS: Eyes wide shut

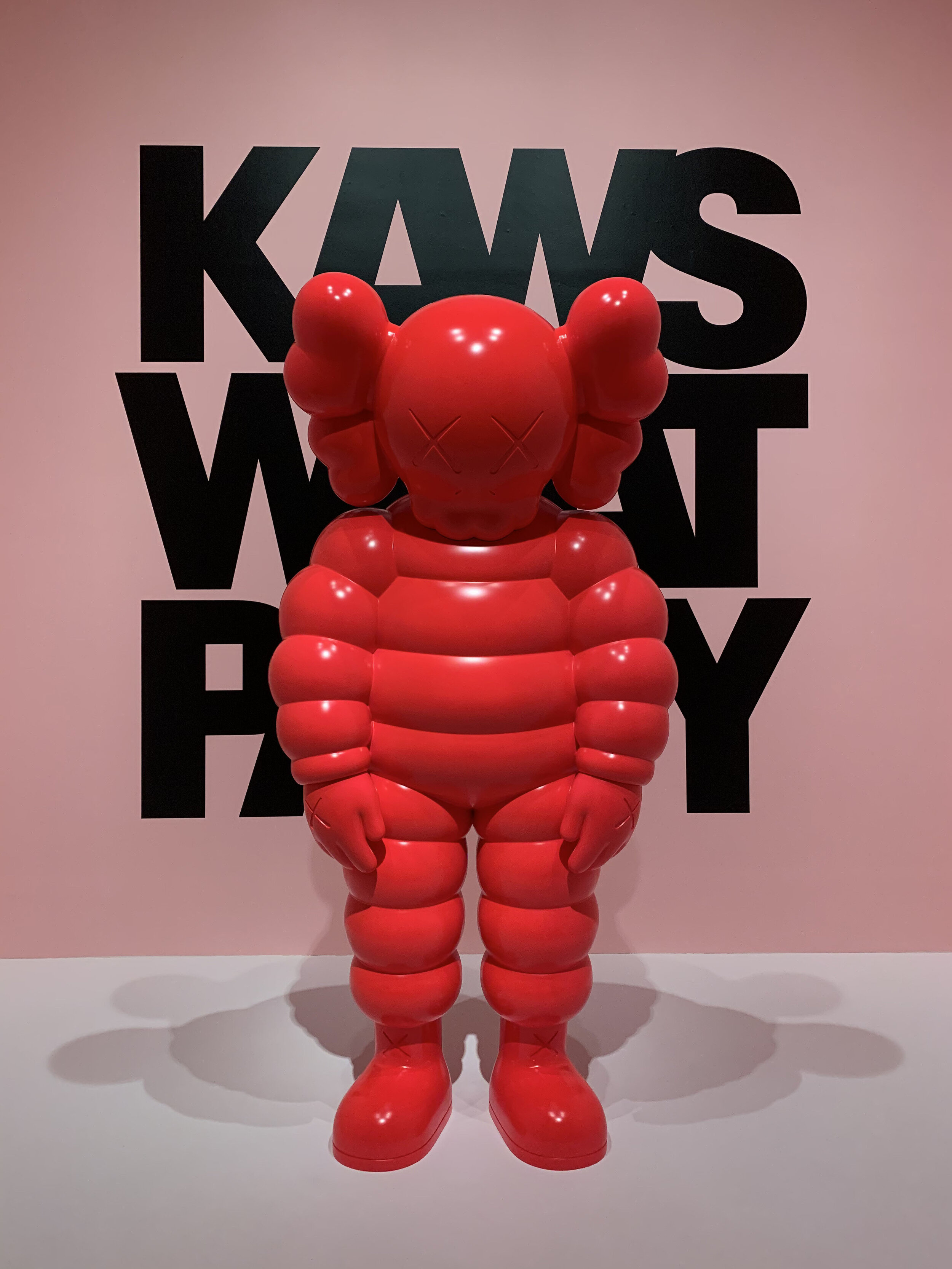

KAWS:WHAT PARTY at the Brooklyn Museum, Iris Krasnopolski for Magpie

By Irina Sheynfeld

Feb. 27, 2021

KAWS: WHAT PARTY is currently on display at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Right by the ticket bunker, clad in what appears to be bullet-proof plexiglass, a colossal, slouching wooden couple, Along the Way (2013), is blindly staring at the empty space somewhere beneath their feet where a ticket line would normally form. Along the Way is one of the latest manifestations of the Companion, a character that KAWS invented in the nineties: two creatures are holding on to each other, supporting and crushing their enormous, polished bodies. At this point in time, with the pandemic still upon us, it is not hard to relate to these exhausted, blind, and faceless effigies.

Untitled (KAWS), 1994, pencil and ink on paper with his tag. Iris Krasnopolski for Magpie

The artist Brian Donnelly, who goes by the name KAWS, first became popular in Asia before he gained the art world’s acceptance in the West. Donnelly earned his BFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York City. He started his artistic journey painting graffiti on various public billboards and telephone booths. Painting on public walls was and still is an act of vandalism or hooliganism (as Adrian Ghenie from our previous article would put it.) One can be fined and even arrested for defacing public property, as was often the case with Donnelly’s predecessor Keith Haring (1956-1990). Following in Herring’s footsteps, Donnelly went to great lengths to make his art accessible to the widest possible audience. In a recent interview with The New York Times Magazine’s writer M. H. Miller, “The Surprising Ascent of KAWS,” the artist recalls how he learned to pick the locks of casings so that he could paint directly on the posters inside bus stop shelters: “I eventually learned how to pick Master Locks in a heartbeat. Probably the easiest lock to pick.”[1]

WHAT PARTY contains 167 objects. As you move through the exhibition, you first encounter Donnelly’s early work: the sharp, dynamic, and strangely elegant graffiti sketches. (Who knew that graffiti are first carefully worked out on paper?) Some of his preparatory drawings look as intricate and elaborate as Celtic knots and are probably the most playful and sophisticated pieces in the show.

The mood of WHAT PARTY darkens when the viewer moves on to the rooms filled with paintings based on various pop-culture characters, such as the Simpsons, SpongeBob SquarePants, and the Smurfs. There is something infinitely sad about these brightly colored works. Untitled (Kimptons #2) (2004) is a group portrait of the Simpsons cast frozen on the couch with a blind stare in front of the TV. In this painting, the Companion’s head is sitting on top of Marge’s and Homer’s bodies. The family members are snuggled next to one another, surrounded by cobalt darkness. There is no horizon line, no perspective, space and time do not exist – the only action is the thoughtless consumption of TV content.

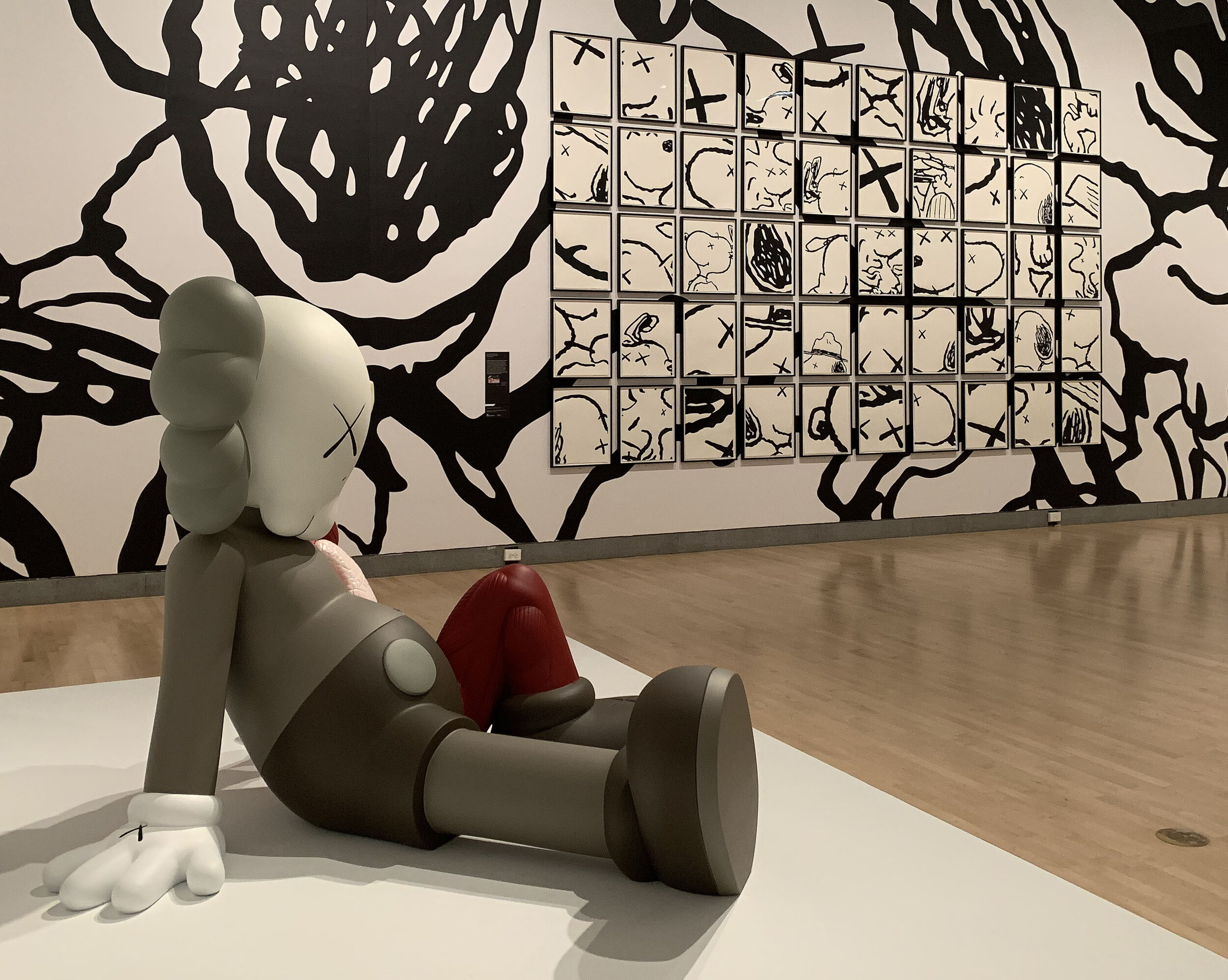

KAWS, Companion (Original Fake), 2011. Iris Krasnopolski for Magpie

KAWS is commenting on contemporary culture through his use of pop icons, but at the same time, he doesn’t resist becoming part of consumer culture himself. It is fitting, then, that since 2012 the Companion has marched in the Thanksgiving Day parade along with SpongeBob, Bart Simpson, and the Smurfs. As Jim Edwards wrote in an article for the Insider, “The figure wears the familiar buttoned britches and shoes of Mickey Mouse. Aside from the shape of its ears, it is basically a dead version of Mickey Mouse.”(2)

As visitors move further through the show they finally enter the realm dominated by the Companion’s incarnations. This post-apocalyptic, post-pop, post-consumer culture planet is a joyless place of dull plastic, flatness, and sterility. The faces of both the giant and tiny figures are subsumed by something like death masks, the eyes X’ed out. Only the figure from Companion (Original Fake), 2011, displays his inner organs, perhaps suggesting that there is more to him than meets the eye. This Companion’s exposed eyeball stares intensely into a world only he can see. He is unable to close his eyelids or look away. What this lonely eye has seen was perhaps so raw and sad that it melted his skin and outer defenses away.

Installation view of KAWS:WHAT PARTY. Iris Krasnopolski for Magpie

In the last room of the show, visitors encounter videos of KAWS: HOLIDAY: a series of monumental projects previously installed in Asia and now projected on three large screens and flanked by four eight-foot-tall wooden Companions. In the center of the room, on top of the round platform, there are four diminutive monochrome Companion iterations: Holiday (2), 2020, Holiday (4), 2020. Donnelly likes to play with the size of the Companion; it seems to represent us, but it occupies its own dimension, either too big or too small for us to enter. Like Alice in Wonderland, we never have quite the right key to unlock the door to its world. In KAWS: HOLIDAY, the character reaches truly epic proportions, often becoming part of the landscape. In 2018, a twenty-eight-meter inflatable Companion floated in Seokchon Lake in Seoul, Korea, and in 2019 his thirty-seven-meter instantiation appeared in Victoria Harbor in Hong Kong. Later that year a forty-meter-long figure was on display at the Fumotoppara Camping Ground in Shizuoka, Japan. The Companion was slated to continue its triumphant march through the world when the pandemic put its plans on hold.

Installation view of KAWS:WHAT PARTY. Iris Krasnopolski for Magpie

Donnelly claims that he got his first break when the New Museum started to sell his toys at the gift shop in the mid-nineties. Around the same time, the artist opened a store in Tokyo, OriginalFake, where he started selling his early art and toys. The current show at the Brooklyn Museum also includes a selection of collectible toys that KAWS is famous for. In fact, many of his young fans are not even aware of his work as a serious visual artist. Some think that KAWS is a brand and not a pseudonym, and they are partially right.

Installation view of KAWS:WHAT PARTY. Iris Krasnopolski for Magpie

Donnelly’s merchandise has a cult following that borders on mania. In Japan and China, his line of T-shirts sells out as soon as they are released. In a 2018 interview with CNN Style, the artist expressed a desire for his work to be available to buyers on all levels: previously limited-edition toys are being released in unlimited numbers. Ten-inch open edition collectible toys are currently sold at the Brooklyn Museum gift shop for $200-$260. The exhibition shop is only accessible for visitors with timed tickets for the show, and the store is selling only a very limited supply of figures per day. Also, an individual can purchase just one figure per visit. Even though I was at the gift shop during the member preview day, before the exhibit was open to the general public, every Companion toy in the display case had a permanent “sold out” sign. The whole process is surrounded by a Free-Mason level of secrecy: the museum staff doesn’t reveal what they have or don’t have on any particular day, periodically announcing to the people in line that they have already run out of everything but posters and T-shirts. During my visit on February 25th, only the lucky few who crossed the finish line to the cash register, after an hour’s wait, were enlightened about the available choices of toys still available on that day. By then, most customers were whipped into a pure frenzy and were ready to buy anything and for any amount. Thanks to Donnelly, the Brooklyn Museum is seeing a flood of fans, young men in their teens and twenties, that had probably never seen the inside of a museum before.

Installation view of KAWS:WHAT PARTY. Iris Krasnopolski for Magpie

What: KAWS:WHAT PARTY

Where: Brooklyn Museum

When: February 26–September 5, 2021

Morris A. and Meyer Schapiro Wing and Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Gallery, 5th Floor

FOOTNOTES

[1] M. H. Miller, “The Surprising Ascent of KAWS,” The New York Times (The New York Times, February 9, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/09/magazine/the-surprising-ascent-of-kaws.html.

(2) Jim Edwards, “Yes, That Was Mickey Mouse's Dead Body In The Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade,” Business Insider (Business Insider, November 25, 2012), https://www.businessinsider.com/kaws-companion-in-macys-thanksgiving-day-parade-2012-11.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cascone, Sarah. “Sotheby's Was Hoping This KAWS Painting of 'The Simpsons' Would Sell for $1 Million. It Just Went for $14.7 Million.” Artnet News. Artnet News, April 2, 2019. https://news.artnet.com/market/kaws-auction-record-sothebys-1505122.

Donnelly, Brian, Germano Celant, and Gary Panter. Kaws, 1993 - 2010. New York (NY): Rizzoli, 2010.

Edwards, Jim. “Yes, That Was Mickey Mouse's Dead Body In The Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade.” Business Insider. Business Insider, November 25, 2012. https://www.businessinsider.com/kaws-companion-in-macys-thanksgiving-day-parade-2012-11.

Holland, Oscar. “Artist KAWS' Giant Floating 'Companion' Appears on Seoul Lake.” CNN. Cable News Network, July 19, 2018. https://www.cnn.com/style/article/kaws-holiday-seokchon-lake-seoul/index.html.

Miller, M. H. “The Surprising Ascent of KAWS.” The New York Times. The New York Times, February 9, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/09/magazine/the-surprising-ascent-of-kaws.html.

Prentnieks, Anne. “Honor Fraser.” Honor Fraser - Artforum International, September 13, 2014. https://www.artforum.com/picks/kaws-48412.