Alexander Calder: A Flight of Fancy

These hesitations and resumptions, gropings and fumblings, sudden decisions and, most especially, marvelous swan-like nobility make Calder’s mobiles strange creatures, mid-way between matter and life.

– Jean-Paul Sartre

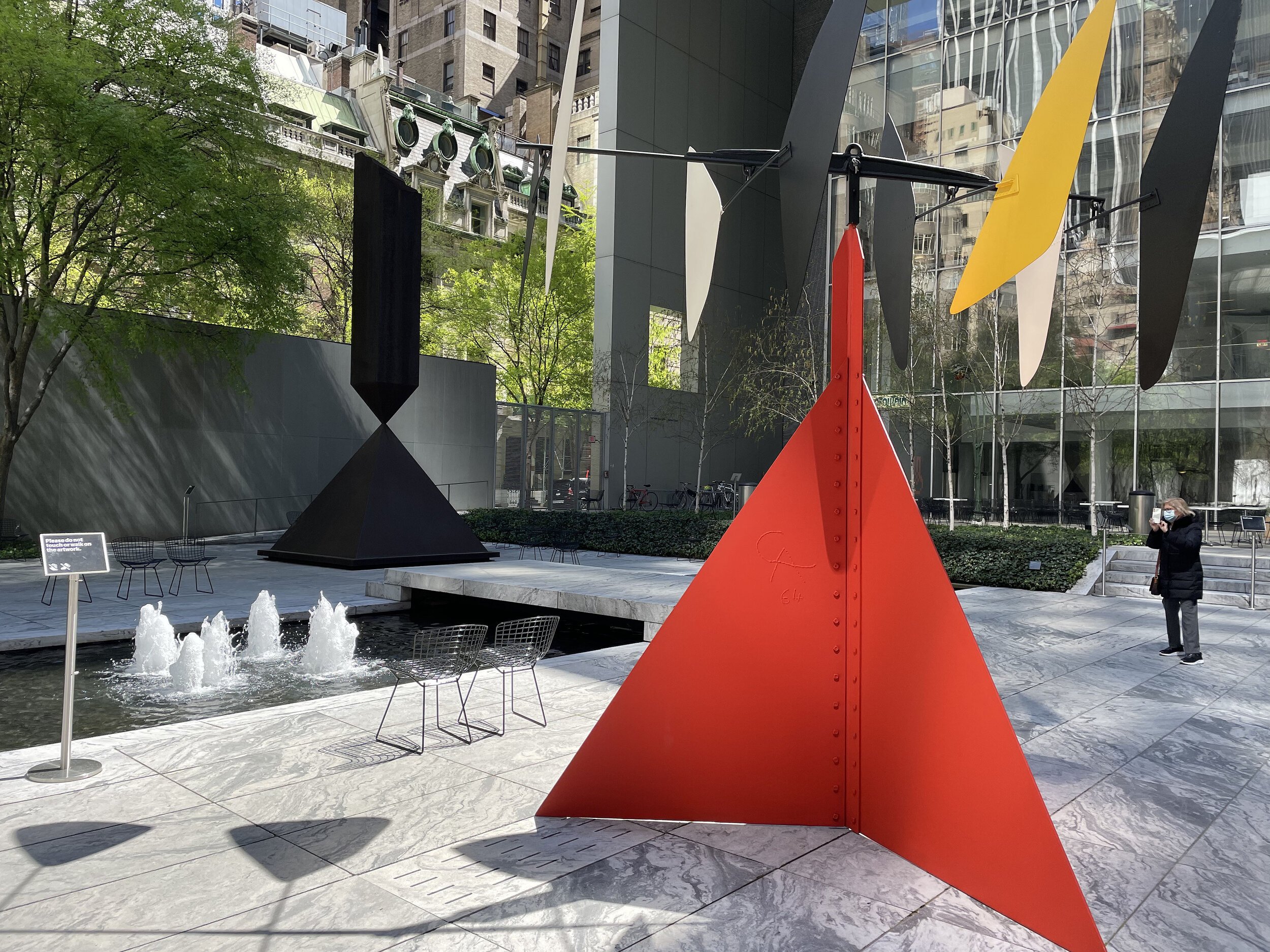

Installation view of the exhibition "Alexander Calder: Modern from the Start", Photograph by Irina Sheynfeld

Alexander Calder’s (1898–1976) life and art is very closely connected to the Museum of Modern Art’s development and growth as an art institution. Museum’s first director Alfred H. Barr, Jr (1902-1981) commissioned Calder several pieces, including Lobster Trap and Fish Tail (1939) located in the museum’s stairwell, and the first retrospective of artist’s work in MoMA was held in 1943. The current exhibition, Alexander Calder. Modern from the start, drawn primarily from the museum’s collection and from Calder’s Foundation, is now on display until August 7. One of the most interesting aspects of this show is Calder’s journey from playful toys, wire sculptures, and wire portraits toward his most recognizable and mature work such as mobiles and stabiles.

Calder’s story starts in Philadelphia, where his father and grandfather were prominent sculptors who created important public works that left an indelible mark on the city’s architecture, both incidentally were Alexanders. Artist’s story continues in Paris, where Calder, known to his family and friends as Sandy, spent his formative years from 1926–1933. In Paris, he started making whimsical, delicate, and poetic wire sculptures and portraits. Some of the sculptures on display from that period are Saw (1928) and Cow (Vache) (1929).

Alexander Calder, Cow, 1929, Photograph by Irina Sheynfeld

In his article “My way: Calder in Paris,” Saymour I. Toll argued that when Calder’ arrived in Paris he was still considering himself a painter, but he soon discovered wire at the local hardware store and started making small figures of animals which he sold to the local toy stores. Calder also began making portraits in wire of his friends – Fernand Léger and Joan Miró and of the famous and popular figures, such as President Calvin Coolige, Babe Ruth and Josephine Baker, a vivacious black showgirl, who at the time, Tall argues, was probably the most famous American in Paris. Calder’s creations were popular among his artists friends from the start and soon he became known as le roi du fil de fer – the wire king. Calder’s wire sculptures were always full of humor, delight and almost childish mischief. Consider Cow that has a long wire that lifts its tail and releases a cow pie. There are countless tales about Calder’s pranks:

While visiting the sculptor José de Creeft, he slipped into the kitchen with pliers and wire and made a wire dog with a hind leg fastened to a sink faucet. When the water went on, the leg went up. In one of his Paris studios, he rigged a toilet to wave an American flag when the lid was opened or closed.[1]

All this frolicking with wire culminated in Cirque Calder (1926-1931), a maquette of the circus, complete with human and animal denizens and various mechanical contraptions. It is currently on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art on the seventh floor. L. Joy Sperling in her article “The Circus and Surrealism,” writes that Circus was “the first truly significant sculpture Calder produced.” After the artist’s first encounter with Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Baily’s, The Greatest Show on Earth, performed in the Madison Square Garden in 1925, Calder was so moved that he painted circus scenes on his bedroom wall. He proceeded to make oil paintings: The Flying Trapeze (1925) and The Circus (1926). It seems that the miniature Circus served as a laboratory for Calder’s later work: a playful world where ideas could be shaped and tested. The work truly came to life only during artist’s performances which he did on a regular basis for his artist friends in Paris and in New York, occasionally he charged admission to help with the rent.

At first the performances were modest: they lasted fifteen minutes and comprised about a dozen acts. The artist sat on the floor to work the figures and to introduce the acts, while an assistant (sometimes Foujita, on at least one occasion the artist Isamu Noguchi, and later the artist's wife Louisa James) operated the victrola that provided background music.[2]

The early wire works that are on display in MoMA, such as Marion Greenwood (1928) and Josephine Baker (III) (1927), were created at the same time as Circus. Calder would continue to experiment with the sculpture that is actively engaged with its environment, movement, and with the element of time, throughout his career. The works such as Cow or Portrait of a Man (1928) still look like drawings in space – they are not yet systems that operates in four dimensions. Yet, these wire sculptures are the precursors to Calder’s most recognizable and imaginative pieces such as Lobster Trap and Fish Tail (1939) and Snow Flurry, I (1948). Standing in one of the smallest galleries in MoMA, dedicated to Calder’s early creations from Paris, it is easy to see how the artist made a leap towards floating mobiles: works that seem to defy gravity, like graceful trapeze acrobats that inspired them.

Installation view of the exhibition "Alexander Calder: Modern from the Start", Photograph by Irina Sheynfeld

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Toll, Seymour I. "My Way: Calder in Paris." The Sewanee Review 118, no. 4 (2010): 589-602. Accessed May 5, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40927519.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. “Les Mobiles de Calder,” in Alexander Calder: Mobiles, Stabiles, Constellations, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Louis Carré, 1946). English translation as “Calder’s Mobiles,” in Sartre, The Aftermath of War, trans. Chris Turner (Kolkata: Seagull, 2008).

Sperling, L. Joy. "Calder in Paris: The Circus and Surrealism." Archives of American Art Journal 28, no. 2 (1988): 16-29. Accessed May 17, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1557510.

NOTES

[1] Seymour I. Toll, "My Way: Calder in Paris." The Sewanee Review 118, no. 4 (2010): 589-602. Accessed May 5, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40927519.

[2] L. Joy Sperling. "Calder in Paris: The Circus and Surrealism." Archives of American Art Journal 28, no. 2 (1988): 16-29. Accessed May 17, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1557510 p.18